Activity Theory in HCI

Activity theory is a framework that can help designers and researchers ask the right questions to resolve their complex problems, but it does not provide a ready-to-use solution. This is unlike a traditional “theory” that acts as a predictive model. In other words, activity theory is more like a meta-theory than a predictive theory.

Here, I briefly summarize activity theory, its origin, and the application to human-computer interaction (HCI). The content is largely inspired by the book: Activity Theory in HCI - Fundamentals and Reflections (Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012).

Activity Theory

The foundational concept of activity theory is “activity”, which represents the interaction between the subject (i.e., the actor) and the object (i.e., an entity objectively existing in the world). A common way to represent activity is “S < − > O.”

Subjects interact with objects to achieve some needs through activities. In this process, activities and the entities (i.e., subjects and objects) mutually determine one another. On one hand, the properties of subjects and objects define the activities. On the other hand, the activities can transform both subjects and objects.

Initial Theory (1920s and 1930s)

The initial version of activity theory originated from Russian/Soviet psychology of the 1920s and 1930s, notably Lev Vygotsky and Sergei Rubinstein.

Vygotsky is known for the “cultural-historical psychology”, which studies the relationship between 1) the mind and 2) culture and society. Two dimensions are significant. The first dimension is external/internal. Human beings use tools to mediate the world, including physical tools (e.g., hammers) and psychological tools (e.g., a map, an algebraic notation, and so on). Such culturally developed tools change the structure of human behavior and mental processes. In many cases, subjects who used external tools (mediating artifacts) to solve a task gradually stopped using those artifacts and transitioned to use internal ones. Vygotsky called this phenomenon internalization. The whole process of solving a task remains to be mediated, but mediated (partially) by internal signs rather than external ones. Note that it does not mean that the internal plane is pre-existing; instead, the internalization creates the internal one.

The second dimension is individual/social (or inter-psychological/intra-psychological). All animals have “natural” psychological functions (e.g., memory, perception), but only human beings have higher psychological functions (e.g., driving, navigation using map). New psychological functions are first distributed between individual and other people; they emerge as inter-psychological functions. Initially, the individual cannot perform the function alone. Over time, the individual progressively masters the function so that they can perform without help from others, namely, intra-psychological.

Rubinstein proposed the principle of “unity and inseparability of consciousness and activity”, which means human conscious experience (internal) and human behavior (activity, external) are closely interconnected and mutually determine one another. To me, this external/internal dimension is easy to be confused with the one in Vygotsky’s work. So be careful.

Alexey Leontiev’s Theory

Leontiev’s activity theory extended the ideas of Vygotsky, a mentor and friend of Leontiev. It is also strongly influenced by Rubinstein, a long-time colleague of Leontiev.

Several main principles are as follows:

- Object-orientedness. All human activities are object-oriented. The objects differentiate activities from one another. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the objects to understand human activities.

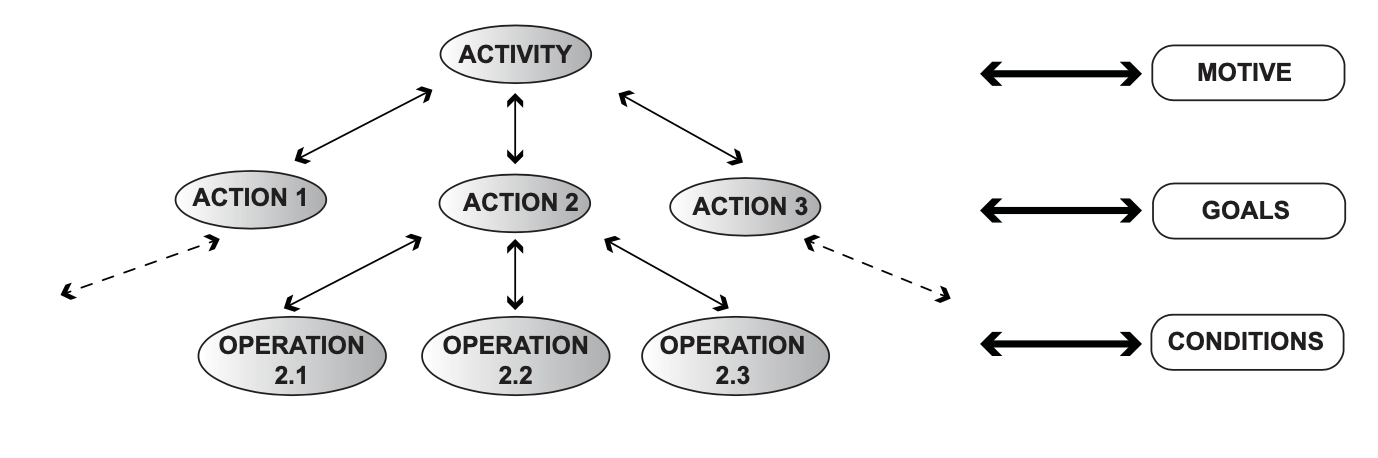

- Hierarchical structure of activity. Human activities can be organized as a three-layer hierarchy, as shown in the diagram below.

- The top layer is the activity itself, which is oriented towards a motive/need (e.g., to enroll in a graduate school).

- The middle layer is the conscious processes called actions to be taken to fulfill the motive, which are oriented towards goals (or even subgoals), such as preparing for GRE, getting recommendation letters, and so on.

- The bottom layer is operations that actually implement actions. Operations are typically non-conscious processes that humans are not aware of them. For example, preparing for GRE requires the operations of reading, writing, and using a mouse. When such routine operations fail, they are often transformed into conscious actions again.

(Figure 1. Three-layer hierarchy of activity. Image credit: Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012)

(Figure 1. Three-layer hierarchy of activity. Image credit: Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012)

- Mediation. This inherits the work of Vygotsky about mediation. Human beings use tools to mediate the world. Tools are influenced by culture while their use also influences the social and cultural knowledge.

- Internalization and externalization. Any human activity contains both internal and external components. Internalization, as discussed above, gradually reduces the presence of external components. In contrast, externalization transforms internal components into external ones, such as sketching a design idea.

- Development. Development requires that 1) any object of study should be analyzed in the dynamics of its transformation over time (e.g, prefer formative experiments to controlled ones); 2) the analysis of development can happen in different levels, such as in biological evolution, in social history, and in phases of life.

Yrjö Engeström’s Activity System Model

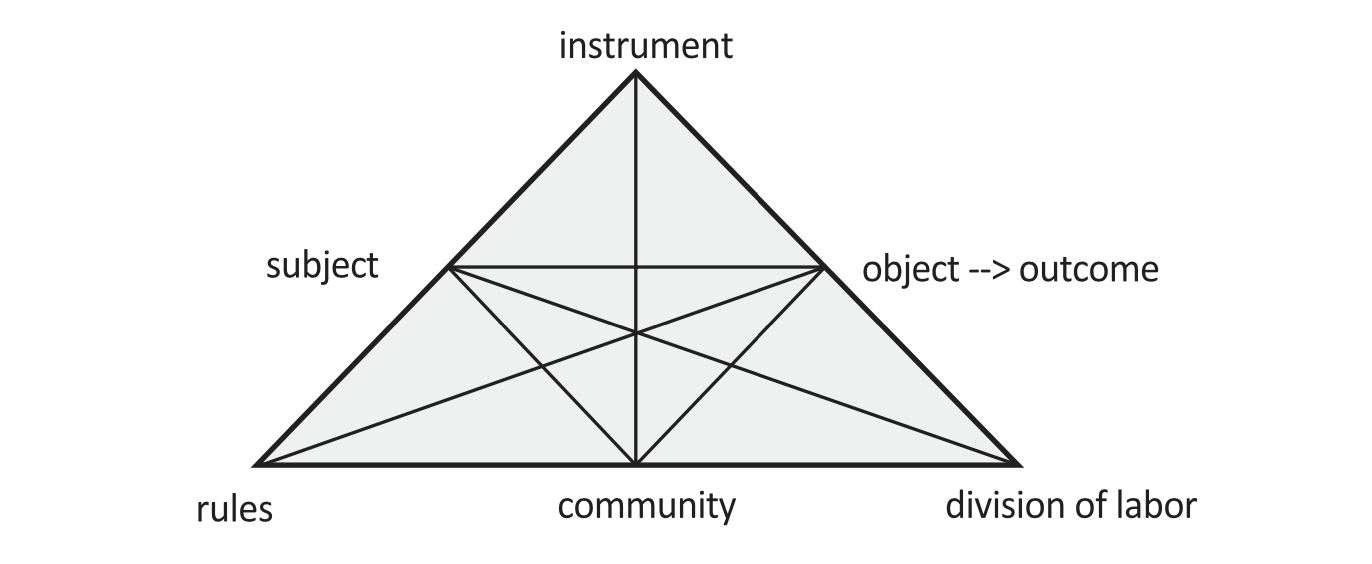

Leontiev’s theory is mainly focusing on activities of individual human beings. Engeström, however, proposed a model for collective activity called “activity system model”.

Two significant steps are extended to Leontiev’s theory. First, the subject-object interaction includes a third element: “community”. These three elements form a three-way interaction; namely, a down-pointing triangle, as shown in the center of the diagram below. Second, each of the three interactions is mediated by a special type of means. Specifically, the instrument/tool is a mediator for subject-object interaction (same as Leontiev), the rules are for subject-community interaction, and division of labor are for community-object interaction. All the elements and means form a large, up-pointing triangle.

(Figure 2. Activity system model. Image credit: Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012)

(Figure 2. Activity system model. Image credit: Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012)

Application in HCI

Activity theory has been applied to HCI by many researchers. Here, I just list two concepts that immediately look relevant to HCI.

The first concept from activity theory is the “subject-object” interaction, which seems similar to “human-computer” interaction. However, it is not so straightforward to apply this concept to understanding how people use interactive technologies. “Computer” is typically not an object of activity but rather a mediating artifact. In other words, people interact with the world through computers. This perspective was reflected in a key book: Through the interface-A human activity approach to user interface design (Bødker, 1987).

The second concept is the hierarchical structure of human activity. The use of computer (or other technology) is often at the operational layer (bottom layer of Figure 1). It is suggested to relate such operational aspects to higher layers, such as meaningful goals and the needs and motives of technology users. Such an extension is consistent with the need of the field to move “from human factors to human actors” (Bannon, 1995).

Final Remark

Initially, I thought I could learn some concrete solutions from activity theory (as a predictive model). However, after reading the book by Kaptelinin and Nardi (2012), I got to know that activity theory is not such a framework. To truly leverage this theory, some more concrete frameworks/theories should be combined with it. If time, I will find some case studies or examples along this line.

References

- Bannon, L. J. (1995). From human factors to human actors: The role of psychology and human-computer interaction studies in system design. In Readings in Human–Computer Interaction (pp. 205-214). Morgan Kaufmann.

- Bødker, S. (1987). Through the interface-A human activity approach to user interface design. DAIMI Report Series, (224).

- Kaptelinin, V., & Nardi, B. (2012). Activity theory in HCI: Fundamentals and reflections. Synthesis Lectures Human-Centered Informatics, 5(1), 1-105.